For some reason I've started re-reading the classic novels of H.G. Wells. I didn't mean to be doing this—I had a plan to read more contemporary work—but the truth is that H.G. Wells, in his stuffy old Victorian way, feels more gripping and, well, provocative than anything written in the past twenty years. That's because Wells, I think, understood that he was writing at a time of moral crisis, while most modern authors still act as if they're writing at a time of moral complacency. Where are the Wellses of our time? We need one.

H.G. Wells, for anyone who's forgotten, is the classic British author who's generally credited with having invented modern science fiction. Other authors sometimes share the credit—Verne, Poe, Shelley—but I'm not sure they deserve it, because they were all essentially writing pre-modern adventure stories. In those kinds of stories, the hero, or antihero, leaves society to have an encounter with the fantastic, while society itself remains unchanged. Wells's stories, by contrast, always turn on a shocking revelation that upends our understanding of what society is. They're not what I would call utopian or dystopian, but they're "topian" in a general sense. They're about looking at humanity from a scientific perspective—and feeling a bit queasy at what's revealed.

This is particularly true of the "scientific romances," as they were then called, that Wells wrote in his most fertile artistic period, from about 1895 to 1905, when Wells was in his thirties. The striking thing about these works is that they break essentially every "rule" science fiction writers are supposed to follow. There's no character development to speak of. No moral growth. There's very little of what we would now call "worldbuilding." All the scientific concepts are absurd. If modern science fiction stories ask "what if?", Wells's stories seem to ask "why not?" Why not build a time machine by sticking levers on an armchair? Why not turn animals into people by cutting them apart and stitching them back together? In Wells's novel of space exploration, two men travel to the moon essentially on a whim, barely pausing to pack a picnic lunch. There's a kind of crazed incautiousness to these books, on the part of the author as well as the characters. Wells's characters are indifferent to danger, and Wells himself seems indifferent to the perils of unconventional storytelling. War of the Worlds, for instance, despite its epic reputation, is an episodic, rather leisurely story set almost entirely in the London suburbs, with a hero who accomplishes nothing of significance and an alien invasion that barely even gets started.

People who study the art of fiction—I mean really study it, in a systematic way, like Will Storr or Christopher Booker—usually seem to conclude that good stories are fundamentally personal. They're built around people, around characters who change, who grow and mature and gain experience and learn to be less egotistical. Wells's stories aren't like that at all. His heroes have essentially no personality. It's often unclear what their motivations are. In some cases they stumble into odd situations for no reason whatsoever. They have basic human urges—curiosity, a survival instinct—but no individuality, no history to speak of, no distinctness. In some books, they don't even have names. The hero of The Time Machine is simply called "The Traveler," and I couldn't for the life of me tell you the name of the hero of The War of the Worlds, even though I'm reading it right now. These aren't the kinds of stories people say they want to read. Yet Wells's novels have been huge successes by any measure. The Time Machine? The Invisible Man? The Island of Doctor Moreau? The War of the Worlds? It's been over a hundred years and they're still making adaptations. What the heck is going on?

I find this disconnect fascinating. It's an implicit rebuke to the legitimacy of literary theory. Ask any reader what it takes to make a good story, and she's almost sure to mumble something about well-rounded characters. What do we make, then, of the fact that stories without well-rounded characters are some of the most successful stories of all time? Not only critics but everyday readers are wrong on this point. I'm sorry, just wrong.

But there's more to the matter. Wells’s stories lack well-rounded characters because, in a fundamental sense, they can't have well-rounded characters. They're specifically and obviously about something else, a subject transcending any mere individual. They're about the human race.

This really pops out when you read a bunch of the books close together. Wells was writing at the end of the colonial era, when a few vast European empires dominated the globe. But he was also writing at the start of the Darwinian era, and at the height of the socialist era, and at the start of the feminist era, when people were starting to take a big-picture view of the human species as a whole. Wells himself was both a Darwinist and a socialist, and his books are full of a queasy kind of species-consciousness, the feeling that what matters in human affairs isn't the dreams of this or that particular person, or even conflicts between groups of people, but the overall plight of the human organism vis-à-vis the natural world.

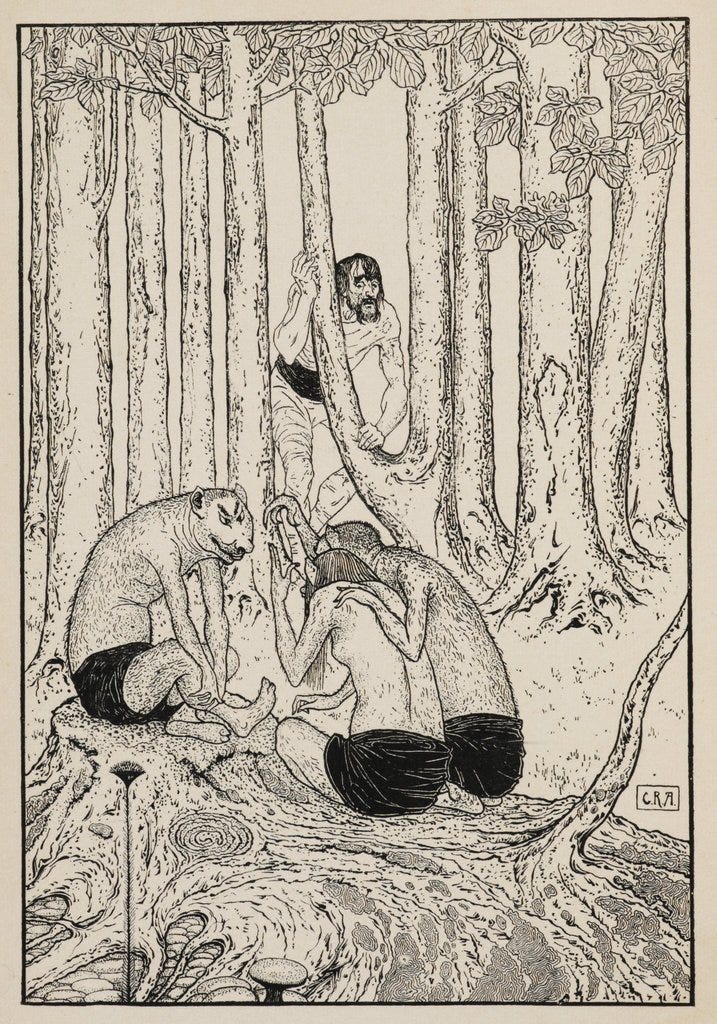

For instance, in The Island of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist who tries to turn animals into people succeeds instead at underscoring the Darwinian insight that people are, at heart, merely animals. In The Time Machine, an explorer travels to the future to find that human beings have evolved into two distinct, degenerate species, predator and prey. In The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth, ordinary human beings are replaced by genetically engineered giants. And in The War of the Worlds and The First Men in the Moon, everyday people come into contact with members of alien species who view the entire terrestrial biosphere as a kind of hostile organism.

It's all just nature—that's the message. People are part of nature. What matters to Wells isn't interpersonal conflict, but microscopic change. The famous twist in The War of the Worlds is that both humans and Martians think they're fighting each other, engaged in a clash of civilizations—when really, as the title suggests, the conflict is between two worlds, two planets, with everything that implies. The efforts of humans, much less individual humans, prove inconsequential to the ultimate outcome—or anyway, not much more consequential than the actions of individual cells. It all comes down to biochemistry.

This basic setup should sound familiar. It's the template for Alien, for Night of the Living Dead, for The Terminator, for Godzilla, for Invasion of the Body Snatchers, for The Blob, for Starship Troopers, for The Thing, for Outbreak, for Deep Impact, for Lovecraft, for Michael Crichton, for a century's worth of disaster fiction. Humans versus bugs. Humans versus mutants. Humans versus microbes. Humans versus extraterrestrials. Humans versus robots. Humans versus reanimated corpses. Humans versus giant monsters from under the sea.

Hollywood has taken the Wellsian formula and added in those well-rounded characters everyone loves; we now expect our disaster-themed summer blockbusters to come packaged with shrink-wrapped stories about estranged dads reconnecting with their families and young girls learning to build self-esteem. But Wells is here to remind us that we don't actually need these tropes in a disaster plot, only the marquee concept itself. These kinds of stories are distinguished solely by different flavors of existential menace. Producers swap out specific actors and heroes every generation, but you can't make a Terminator movie with terminators, or an Alien movie without acid-bleeding xenomorphs, or a Jurassic Park movie without man-eating dinosaurs. For that matter, you can't make any of these movies without humans. They're stories of species-on-species conflict. It's Darwinian struggle, all the way down.

This is what makes the Wellsian template different from, say, a story like Frankenstein or Dracula or Avengers: Infinity War. Frankenstein is a character. Dracula is a character. Thanos is a character. They’re villains, with individual, villainous aspirations. The Wellsian menace lacks such motives. It serves a metonym for nature as a whole, and might be as concrete as a big tumbling space rock or as vague as a natural law. The point is that, with respect to such an adversary, humans aren't really human at all. We're lipids and proteins. Cell walls and cytoplasm. Meat and blood. Math and code.

Here's the thing. The Wellsian moment is over. We processed and internalized its central revelation. We accommodated ourselves to the Darwinian shock that people of Wells's era faced. And now we're facing a new kind of shock, and we're going to have to find new ways to process it.

In a sense, the Darwinian crisis Wells was writing about amounts to a form of species-wide humiliation. Humans are organisms. Deal with it. Well, it was hard, it was a difficult adjustment, but now we've mostly dealt with it. We came up with a different kind of story, one that emphasizes adaptation to the Wellsian message as its own form of heroic achievement. Hence the disaster-movie trope of the Cassandra-type figure who survives precisely because he or she recognizes the impersonal nature of the threat—who gives some version of Michael Biehn's speech in The Terminator:

"Listen and understand. That Terminator is out there. It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop, ever, until you are dead."

The hero of the post-Wellsian disaster story is a man or woman—or sometimes a robot—who refuses to entertain romantic illusions about the nature of the species-wide struggle to survive. She's a scientist who pleads with heads of state to recognize the nature of the planetary threat. She's a girl who pleads with her oblivious boyfriend not to poke the strange cocoon in the basement. He's a chaos theorists who warns arrogant scientists that nature is not a toy.

Look around online, and you can find thousands of people desperately trying to be such a hero. The lone voice of reason. The puncturer of illusions. The myth buster. The data nerd. The critiquer of false narratives. The seer-througher. The conscience of the race. The brave disenchanter.

To what end, though? If anything, this widespread urge to play the unsung prophet of doom has itself become a major contributor to our problems. It's not just that people keep shouting and shouting without ever managing to get anything done. It's that the shouting never accomplishes its purpose. We can't help but feel an irrational need for meaning, even in the face of existential horror; we can’t help but remain stubbornly enchanted. Even the shouters themselves are acting in accord with a mythical imperative, competing to present themselves as uniquely perspicacious harbingers of apocalypse. Humans may be a part of nature, we're a part of nature that needs to feel a sense of unscientific wonder. If, at bottom, we're engaged in a species-wide war of attrition against chemicals and microbes and the forces of entropy, it’s in our nature to wage that war by coordinating around inspiring ideas. In that sense, we're a supernatural species after all.

Here's another way to look at it. Much as new techniques of observation forced us to face up to unpleasant facts about human biology, the internet is now forcing us to face awkward truths about human psychology. I used to think the ugly dynamics of online behavior could be traced back to features of the online environment itself, or to specific political philosophies, or to certain technological affordances. But I'm coming around to the view that the internet, instead of altering human nature in pernicious ways, is showing us what human nature was really like all along. We’re learning more about ourselves than we ever wanted to—we’re learning that narcissism, far from being a unique affliction of modern times, is in essence the default human condition. We’re all sick, we’re all crazy, we’re all hopelessly self-involved. We’re bad, bad people, deep inside, and the pain of knowing this makes us worse. If the technologies of Wells’s day disabused us of certain theological illusions regarding our place in the natural world, the technologies of our own day are now reminding us that we’re still just wretched sinners, after all.

How will we learn to cope with this new crisis? Who is the H.G. Wells of our moment? What new stories are we going to tell?